You Done It

Info

Project type: Godot Networked VR/Flatscreen Game

Timeframe: 2 Months, 2025

Team: 2 Artists, 2 Designers, 1 Programmer

Team-Immerse-Yourself/YouDunIt.git

Product Overview

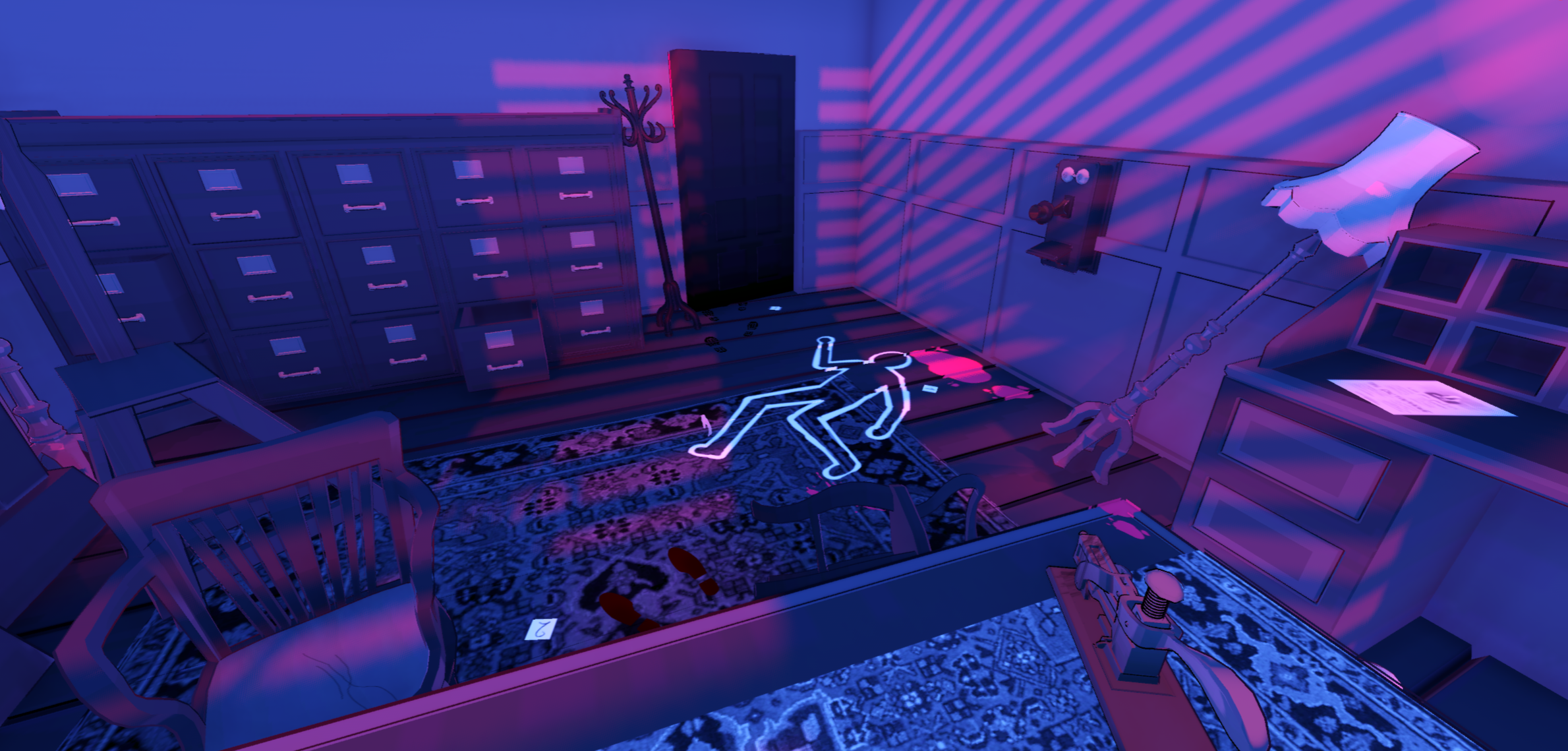

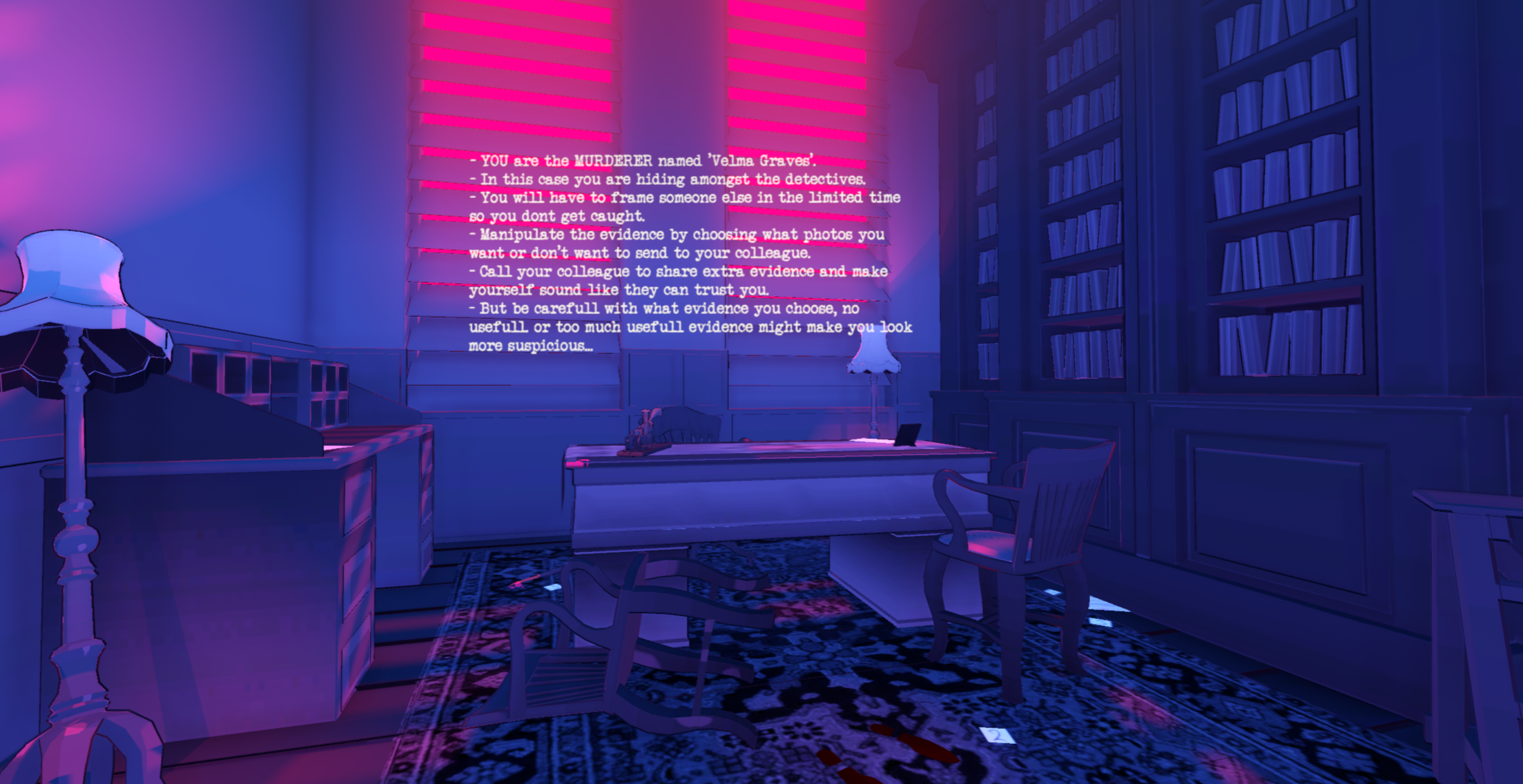

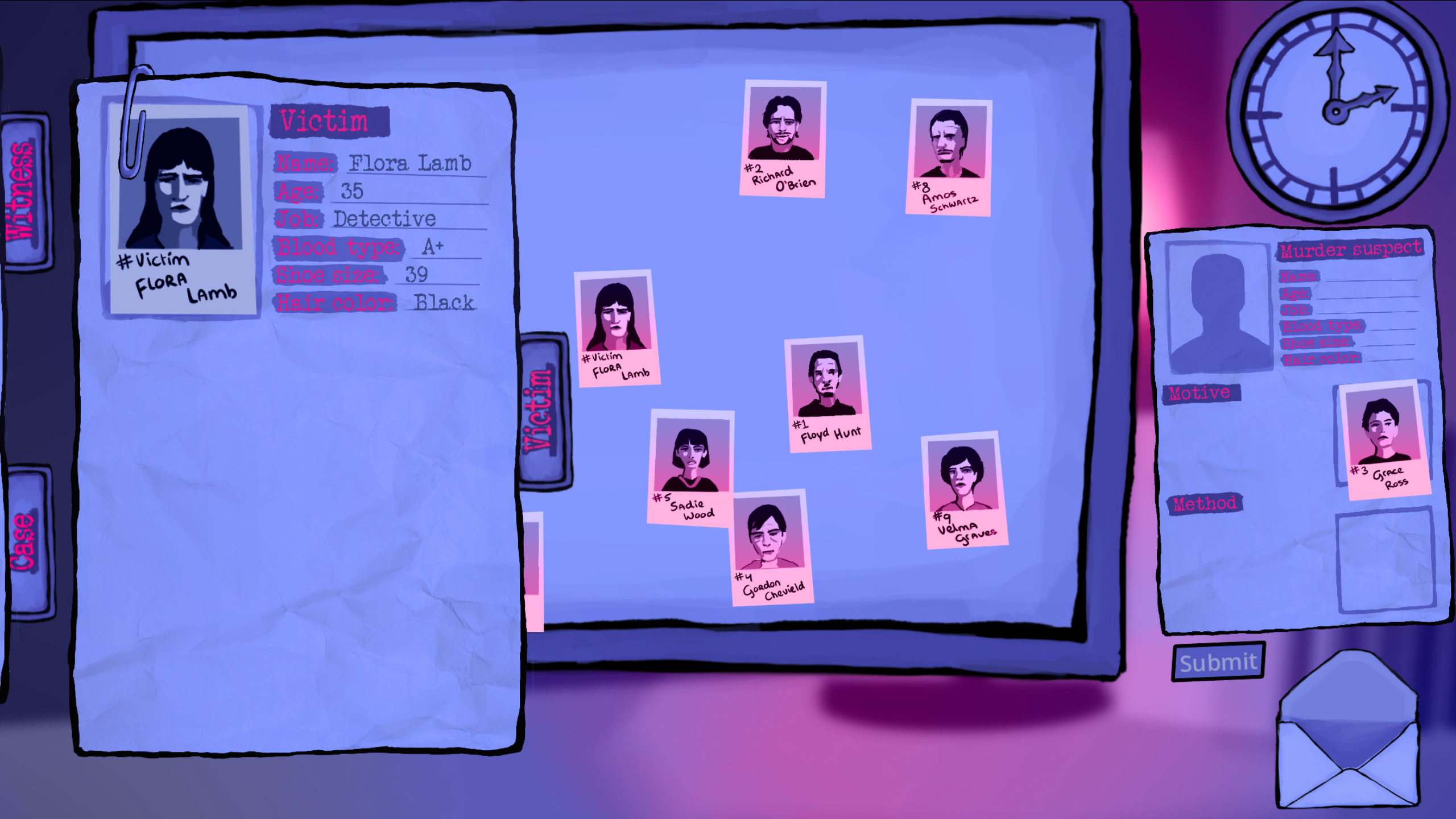

A two-player multiplayer game about manipulating information. One player needs to restrict what the other can see to get away with murder. The second player needs to figure out the full story from the objectively observable facts and the testimony of the first.

Project Overview

I was the only programmer on this project, meaning I worked on both the VR and flatscreen interaction code on top of the communication and networking.

Postmortem

The concept, a two-player asynchronous multiplayer game. Was extremely interesting to work on, it came with challenges that don't have to be considered at all on any other kind of game project.

Separations

Although not my first choice of medium, I do still have a latent interest in the technology of VR. It has opportunity for probably the most varied interactions of any "video game" medium. But that level of interactivity also comes with a major development workload that the team we had was not equiped to handle. So our first step after deciding a concept was to limit interactions. So the player is only able to walk around (physically, so there's no controls needed, just a large space and a long cable). And the player can't really pick anything up other than the camera, which is glued to their hand.

Limiting the workload for the VR interaction freed up a lot of time. Which was needed to also be able to make a whole second game at the same time. The second game is a 2D UI-driven affair, and thus much simpler to implement. The hard part was working with shared concepts. Because they need to represent the same ideas, the two "games" share a codebase, letting them share definitions of low-level networking primitives such as message type IDs, error codes, and data structures. This ensures absolute consistency between client and server.

The core systems of the game, including these primitives and the shared concepts of the games, are all implemented as an engine module. Meaning they are compiled as part of the engine executable (an advantage of godot being open source). This simplified managing the two versions of the game massively, as the executable only needs to be built once. Switching between the different versions simply means giving the executable one .pck file or the other.

Aside: Code and Data

In my technical design I separate all features, bugs or issues into "code" and "data" responsibilities. Data responsiblity is generally "Ways the game can be affected from the editor". Which usually means "Anything that affects the game that isn't code". Meanwhile Code is what directly defines the outcome or interpretation of Data. This definition implies that Data depends on Code to have effect. While the inverse is not necessarily true. But I do keep a hard rule I for myself, that Code cannot depend on Data. Code is not allowed to break because of absence of or fault in Data. This means that any Code that directly deals with Data should be written with extra care to be especially fault-tolerant, and preferably even fault-correcting. To avoid passing faults down a dependency chain. Whereas when Code problems are detected, my preference is to hard-crash to desktop (or debugger), as faults in code can lead to much worse consequences for the user, and hard-crashing means that the problem must be fixed before shipping anyway.

The two definitions I use mostly come down to the same thing. But some engines, like Godot and Unreal split them: they have editor-accessible scripting languages (GDScript and Blueprints). Which, by the first definition implies that scripting, despite being code, is a "Data" responsibility. This is a good thing. Because the first definition could be rephrased as "things I want a designer to be able to modify" which absolutely goes for script logic. Letting (technical) designers write scripts is an extremely advantageous part of any larger project workflow. But, scripts being Data, increase Code workload. Because suddenly all script-accessible interfaces have to be treated as suspect. Anything a script can directly access has to be either explicitly marked as dangerous, or extremely fault tolerant.

Networking

The client and the server are both multithreaded, using the STL native threading objects. Both use the second thread to receive data and respond to messages from the other. The server also uses the second thread to regularly send a heartbeat signal to the client, ensuring that the connection is still alive.

Client

The client of the network is the VR game, as it is generally the piece of the puzzle that "sends" information to the server, which is in control of the game state. Before the game initialises the VR display, it launches into a simple flatscreen UI where the player can type in the IP adress of the server, as typing numbers in VR is a fresh user experience nightmare.

Once connected, the game starts the VR scene, which contains the player node that sets up the OpenXR API. The game will now be rendering to the VR headset. From here on most of the remaining logic is managed through scripting, as most of it amounts to checking input and passing events to native C++ APIs.

Server

The server of the network is the flatscreen game. It boots into a short info screen with a button which, once pressed, opens the 6667 port and starts listening for connections. Once a client sends a

MSG_CONNECT

message, the server responds with

MSG_OK,

which completes the connection flow. From now on all connection requests are responded to with

NOK_OUT_OF_CONTEXT.

With the connection established, the actual gameplay scene opens, and the game proper starts. From this point on the server thread will send

MSG_HEART

and expect

MSG_BEAT

in return within a short time, if no response is given within the expected time the connection is considered lost and the game stops.

The primary gameplay message is

MSG_REVEAL.

This message is sent by the client when the VR player has taken a picture of an object and decides to send it to the other player. MSG_REVEAL comes with a serialised

ClueID

attached, which is deserialised and stored in a buffer. Every frame, the main thread

will lock this buffer and copy it

.

Afterward it will handle whatever was copied, if anything.

The final message sent between the server and client is

MSG_CONCLUSION.

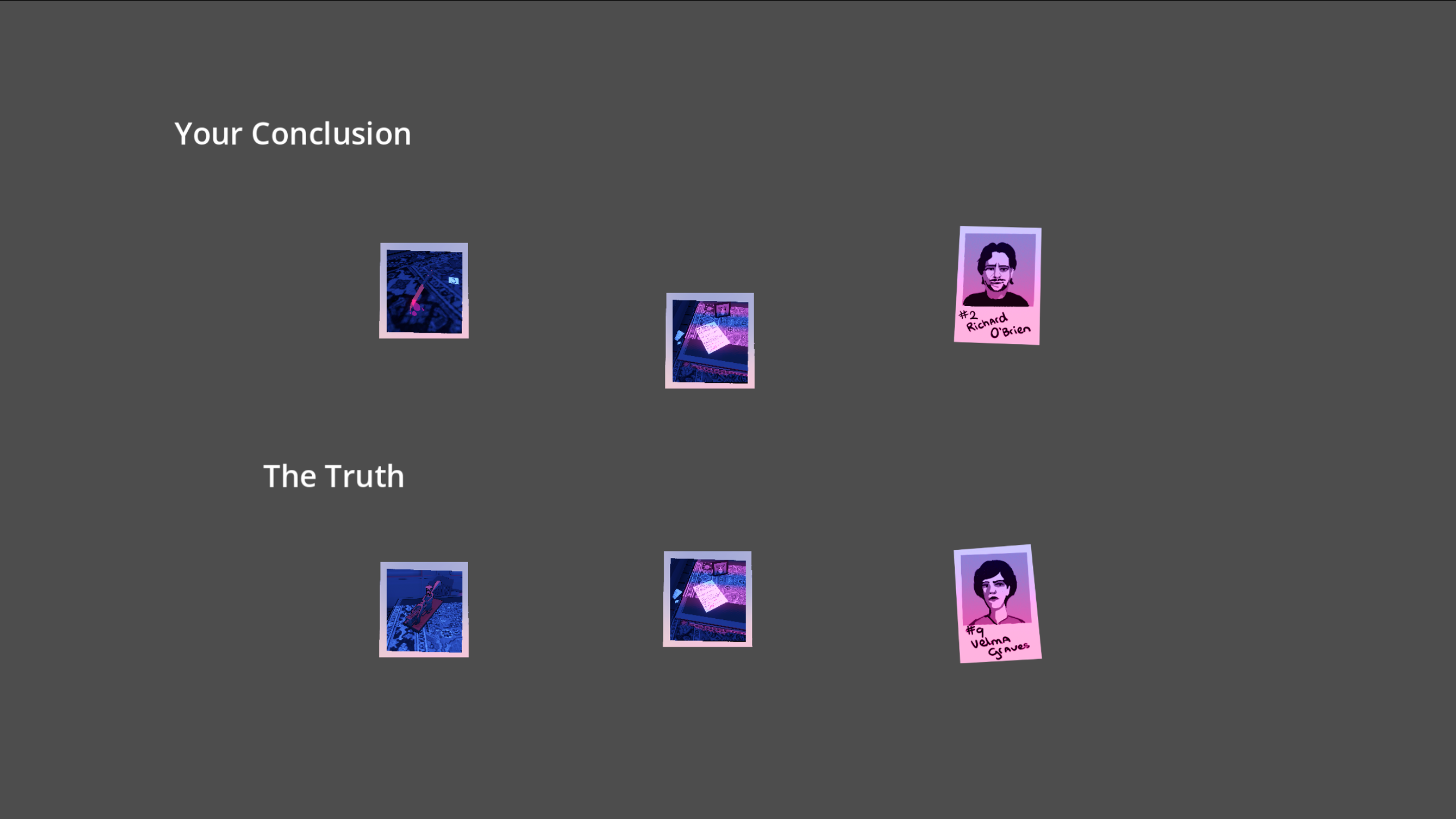

It is sent by the server when the flatscreen player believes they know Who Dun It. At first this was only possible if the player had selected all three parts of the case (Murderer, Method, Motive), but testing showed that that made it too easy to win on a technicality. Where the flatscreen player knew who did it, but was missing one clue needed. So this was changed to allowing a submission if the player has entered any clues in the case file.

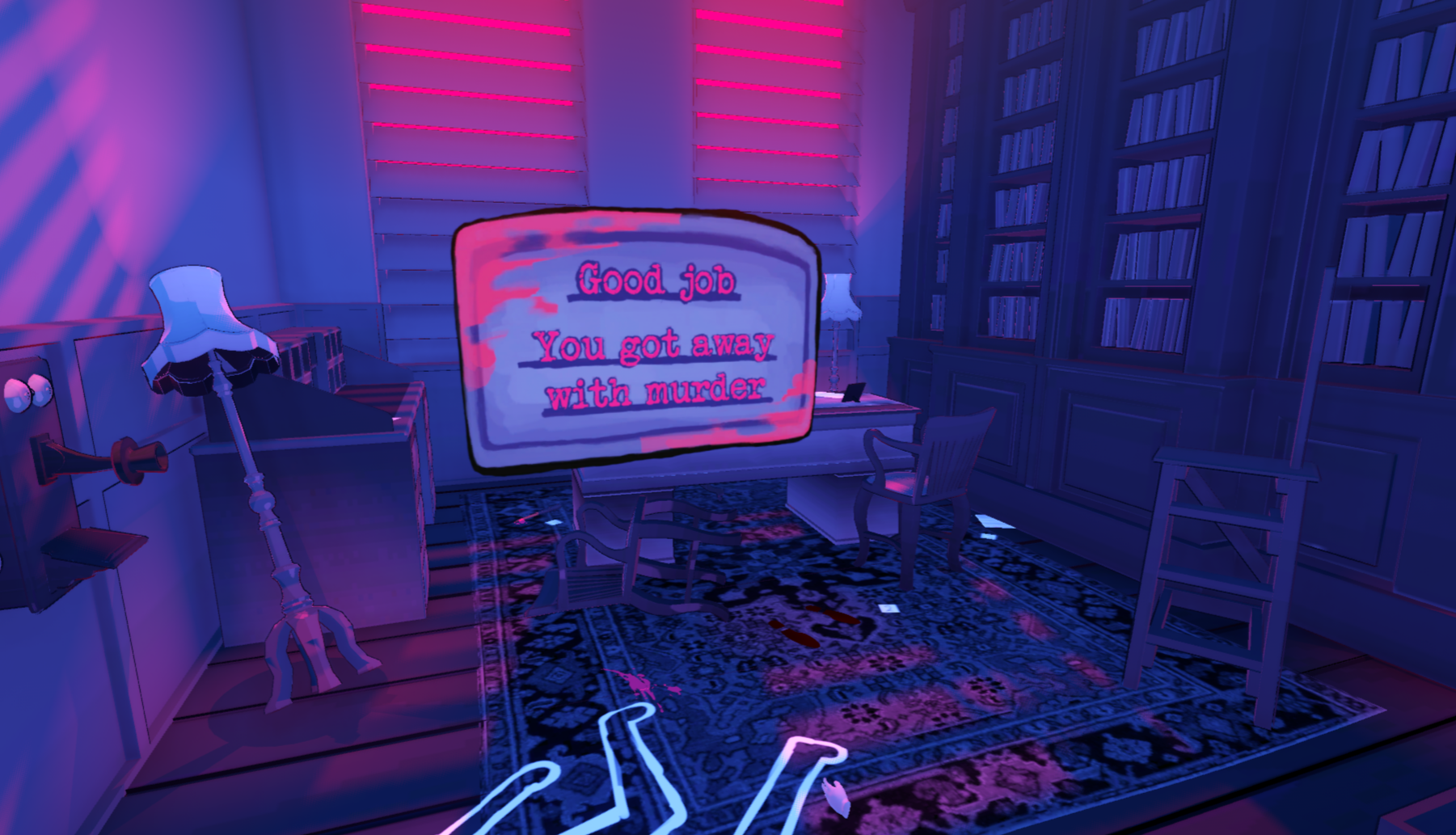

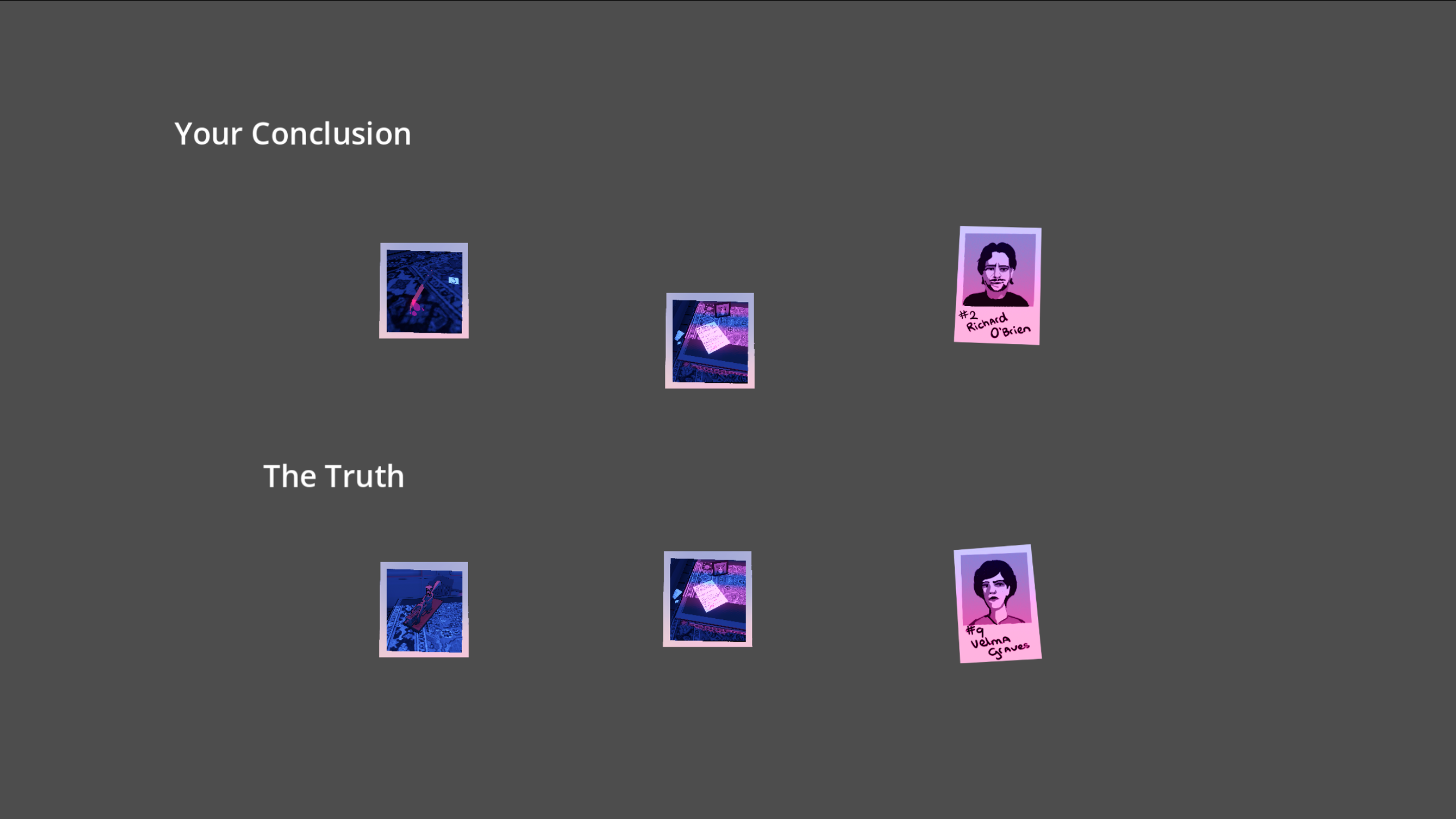

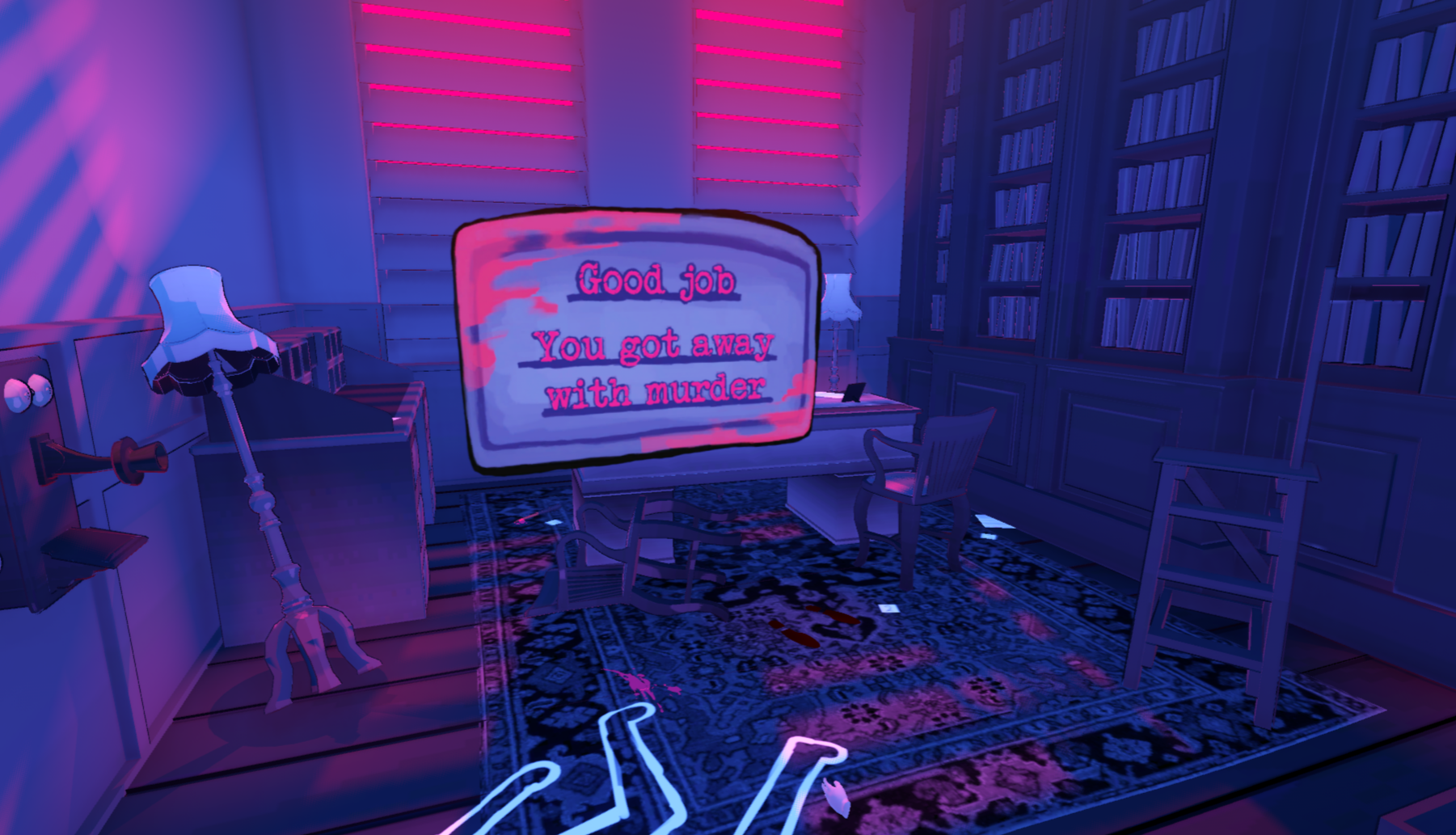

Once the client receives MSG_CONCLUSION it checks if the ClueID sent for the Murderer is correct, and displays the player a message telling them whether or not they won. The flatscreen player is given a similar screen, showing them which of the three clues they submitted, if any, were correct.

Takeaways

I learned a lot from this project. Prior to it I had done a lot of toy projects practicing performance-sensitive multithreading and networking using 0MQ, and this was the first project with actual stakes where I could use the networking part. The multithreading is simple, and not particularly performance-sensitive, but the practice I'd had meant I was far more confident and comfortable with using it. While the knowledge I'd built up in 0MQ networking turned out invaluable to the success of the project.

In the end there wasn't much space to release it to a wider public, as the technology and implementation ended up being too specific to the context in which we exposited it. A more complete release could probably be made, but the game turned out too simple to really be worth releasing that way.